And in the end, things happened quickly.

After years of protracted silences

& painstakingly unmended fences,

we both woke to an email finalizing

the divorce.

Neither of us knew that this would be

the wished-for day. She woke in our house,

I in my shabby place, grousing

internally about the other, replaying

old arguments.

And now there was nothing left

to divide, nothing to fight over.

Fees prepaid. A finally-shut door

kept us safe & far far from one

another.

On opposite sides of town,

the baristas told us,

"Have a nice day."

"You too."

"You too."

This was written for a National Poetry Month challenge, an April Fool's Day poem, something untrue. Sometimes when I write about me & my wife, I use that image, William H. Johnson, Café (ca. 1939-1940) but not always.

-

-

Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead won the Pulitzer in 2006. It is a patient novel that will make you wish you were the intended audience. The conceit of the novel is that the aged narrator, the reverend John Ames, is writing to his seven-year-old son. The “you” of the novel is decades from reading or understanding the story we navigate. For a novel about a man who never leaves his small hometown, Gilead is a wandering novel. It luxuriates over the smallest of domestic memories, some of Ames & his young son, some of Ames & his much younger wife before the birth of the son, some of Ames & his own father, some of the struggle for the soul of a nation during abolition. Robinson’s Ames does not move chronologically, but instead according to the whims of the heart, captured between meals & naps, sermons & visits with an old friend (also a reverend).

The novel is a thoughtful meditation on faith & family without ever sounding preachy, even when it is literally about preaching. It is a subtle almost elegy to a kind of living that few Americans might want in a part of America where few people stay, but it never descends into simple nostalgia or broad critiques of modernity. It is literally a love letter.

*

John Darnielle is the lead singer & songwriter for a band that I don’t listen to often. Eight or ten years ago, his debut novel Wolf in White Van got on my radar, and I picked up a digital copy, which I forgot about until recently. The cover gives you a sense of part of the plot, a washed-out maze. The protagonist / narrator Sean is the designer & curator of a mail-order game with nearly-infinite possibilities, some of which are subterranean. The narrative keeps several things at bay–the ultimate end of his game, for example, or the relevance of the novel’s title. The most unsettling of these mysteries is Sean’s facial disfigurement, a fact of his life so central & apparently so far back in his history that Darnielle withholds the reasons for the disfigurement.

It’s a novel that answers the whys of the lives of its isolated characters. And the answers are rooted in a certain kind of youthful rootlessness, a certain kind of youthful isolation that is the stuff of many American novels, but few novels so unforgiving in their resolutions. But Darnielle is true to his protagonist in shaping this kind of labyrinth of shared loneliness, of the power of the imagination to make despair nearly livable.

*

Years ago, a friend recommended the novel Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice. I wrote back then that it was tragic how with covid it had become such a timely novel, one in which an Anishinaabe community gets cut off from the rest of the non-res world, inexplicably: no power, no communication, no food deliveries to their local store, no radio, no cell phone coverage, no internet. Rice centered that survival narrative on Evan, an able and virtuous and brave member of the community.

With Moon of the Turning Leaves, Rice returns to Evan & his community twelve years after the catastrophe. They have moved from their reservation home to a community in the north. After twelve years, food supplies & wildlife are dwindling; a search party sent out years earlier has never returned. Evan, his daughter Nangohns, his old friends Tyler & JC, and two younger community members Amber & Cal form a reconnaissance team to walk toward their ancestral home & hopefully return with news of that they can relocate. As with Crusted Snow, this novel’s language is direct, and the action is at turns both suspenseful & tender. So very clear about the fear & urgency of living in a world with dwindling resources, it’s very clear about racism & man’s inhumanity to man, and also clear–and optimistic–about the power of ceremony, of language, of family, of ancient skills & endurance of this brave and eternal people. Most reviewers name-check McCarthy’s The Road, which is a little sparse & unforgiving in comparison. Like The Road, however, Rice’s Moon of the Turning Leaves resolves with a hope & a rejuvenation in nature that is well-earned by its characters & welcomed by its readers.

*

Vinson Cunningham worked on the Obama campaign right out of college. His novel Great Expectations is about David, a young Black man working on a presidential campaign right out of college. The Candidate in Great Expectations is clearly Obama, although never named Obama. The unnamed celebrities, movers, & shakers populating the novel are … you wonder why Cunningham does not say “Quincy Jones” or “Jay-Z” or whoever as readily as he says, for example, “Peter Yarrow of Peter Paul & Mary said [some cringey borderline prejudiced thing]”.

David’s coming of age happens in a believable if not always smooth braiding of influences & challenges. His campaign-trail hookups give the reader a sense of the freedoms & releases endemic (perhaps) high intensity hope & change minded young people. His apprenticeship & eventual high-profile status within political fund-raising have a gossipy reality, including the indictments we should have seen coming a mile away. His personal life as a son & new father are … less skillfully narrated & woven in, often delivered as post-coital currency, his part in a quid pro quo of Cunningham’s [ahem] David‘s social climbing. Perhaps the Obama campaign has an iron-fisted NDA, but I can’t help but feel like this book would have worked better as a memoir than as a novel.

*

Greek Lessons by Han Kang is one of those novels that teaches you how to read it. I bought it because of the cover, which does not hint at the fact that it is a novel about two people struggling with being able to understand & be understood. If I had read the inside flap or any of the reviews, that two-person path would have been quite clear. Instead, I was thirty or forty pages (maybe more) into the novel before I realized that it was impossible for this to be a narrative about one person. That thirty or forty pages (maybe more) was a real trip, though, as I was imagining this as a single story.

Which, of course, in some ways, it is.

*

I am rarely disappointed by a publication from NYRB. So I was excited to pick up J.L. Carr’s novella A Month in the Country. It’s a gentle story about gentle people. Even the not-so-nice people are shaped with empathy, with care. The month in the country is devoted to a single job performed by Tom Birkin, a veteran of the Great War, an unveiling of sorts.

Still shell shocked, Birkin works alone over a summer to uncover, inch by inch, a medieval mural in a country church. A fellow veteran works alone in the churchyard, searching for the rumored remains of a country family’s ancestor. Reverends & station masters, daughters & wives populate this country novella with intensity & yearning. War & judgment, marriage & history, art & faith loom large, but only large enough to fit in the open hearts of Carr’s characters. A gentle, beautiful, artful, thoughtful story that [warning: cliche approaching] you will not want to end.

-

Since our department added narrative nonfiction as a required class a few years ago, I’ve read a lot of memoirs lately. In many cases, what draws me in is what I hope to guide my students through — namely, a reckoning with one’s origins. Sometimes these kinds of stories are steeped in trauma, in exile. Lately I’ve read that kind of story so often that I feel like I can recognize the tropes, the beats, even the surprises in those memoirs. I hope that is the sign of a perceptive reader rather than the sign of a skeptical or jaded one.

Ingrid Rojas Contreras shapes an origin / ancestral story that truly had me in suspense and in its thrall. The Man Who Could Move Clouds: A Memoir is a sort of quest, a righting, an answer to the request of their deceased grandfather, a renowned curandero.

What’s unique, primarily, about the memoir is the detailing of inspiration. I mean “inspiration” literally — Contreras & her family are spirited beings, spirit-readers, spirit-talkers. Her family story draws upon pre-colonial Colombian ritual & wisdom without ever losing the challenges & hauntings of the present; her story of the present draws upon the century-long conflicts & disappearances of Colombian history without ever losing the apolitical heart of the story. Nono, the grandfather curandero, has visited his daughter & Contreras (his granddaughter) asking to put to rest — except that he’s been dead & buried for years.

At the heart of the story is a doubling. Contreras & her mother look so much alike that family & friends alike constantly remark on it. Contreras & her mother have suffered / experienced a kind of amnesia that leaves them in some small way separated from themselves & linked to spirit voices & truths.

It’s complicated. It’s … you’d call it magical realism, if Contreras were not there to tell you that to Colombians, this is simply their realism. It ends with the kind of peace that, while impermanent, is lasting enough for most of us.

I often judge books by their covers, which often works out, as it did when I picked up Godshot by Chelsea Bieker. It’s a story set in (but not deeply precise about) climate crisis, a current-day drought-affected California rural community; it’s a story with character driven by (but not deeply probing about) a current-day American brand of Christian apocalyptic male leader ego & charisma. Bieker depicts the ways that the protagonist Lacey May must live within the strict boundaries imposed by the drought & by her Pastor. Family dysfunction & adolescent ignorance is balanced by a sort of wounded mother character on the outskirts of Lacey’s town–the proprietor of a phone sex business. There are forced impregnations, baptisms in soda in lieu of water, shabby trailer & apartment living, and even a kind of shootout or two. It is not pretty, even if it is often darkly funny. I worried that in enjoying this novel I was participating in a sort of class snobbery. Were it not that Bieker has affection for her characters (enough that good things happen to the mostly-good and bad things happen to the mostly-bad), I might have had a really sour taste in my mouth after & during this novel. But it somehow works.

Blackouts by Justin Torres is a provocative & thoughtful novel, artful & deeply moving. Torres’s protagonist / witness (the pseudonymous Nene) is a queer sometimes hustler visiting a decades-older Juan Gay, who is clearly dying. The action of the novel is not about conflict resolution but instead about blackout unveiling. Nene listens to Gay reveal an oral & lived & academically bowdlerized queer history.

As a child, Gay was effectively adopted by a queer researcher, who renames herself Jan Gay, and her beloved, who also renames herself & who uses Juan Gay as a model for her children’s book illustrations. The research Jan Gay conducts is thorough & personal, given her ability to interview subjects as a fellow queer. Knowing that her work will be published only under the co-authorship of a traditional academic, Gay opens herself & her subjects’ lives up to academic scrutiny, misinterpretation, & eventual erasure–the research becomes published in near-unrecognizable form & intent under the title Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns.

I’m making this novel sound very bookish–it kinda is, but it is more erotic than sexual, more about friendship than eros, more about the desire to know & love than to transgress. Juan Gay’s storytelling draws upon Nene’s own rash exploits & johns, upon academic rigor & image, upon Berlin bohemianism & Puerto Ricanness, upon flashbacks & rereadings. It is the kind of novel that makes you feel more empathetic & intelligent, more aghast & awakened with each page.

-

Ruben Quesada, Milky Way in Joshua Tree, July 2022 The first people created were far too large, modeled after the gods themselves. Their uprising was inevitable & ferocious; it saddened the gods deeply to kill these other selves.

The second people created were far too small, no match for the beasts & the birds, far too vulnerable for the elements & the water. The gods, deliberate in their design & construction, were nonetheless confused by how weak these small things were.

The third people created asked far too many questions, looked too deep into divine will & natural law. The gods agreed quickly to kill them in their sleep. Good riddance, they said. Centuries passed with the gods mostly happy with things as they were until a child fell from the sky.

The gods, alarmed by the fiery streak in the sky & the distant thud, rushed to probe this latest remnant of the heavens. Soon they halted their approach, ambrosia’d mouths agape — it was not the celestial boulder they had come to expect but instead beauty in motion. Two ears rather than one, two eyes rather than eight, one mouth rather than two. Limbs lithe rather than warlike, and most importantly, a proportion that fit the landscape — the beasts below him, the trees above. No god dared to say what they were all thinking: This creature in every way exceeded centuries of divine skill & taste, imagination & will. If gods prayed, one of them would have said that this star child was clearly the reward for long unanswered prayers.

The star child arose slowly, eyes wide on the surrounding gods. One god plucked a nearly-ripe fruit from a tree, tiptoeing closer as the child gulped. The god kept his honeyed eyes on the child, ignoring the iridescent lock of hair of hair fluttering across his face, his eternally powerful hands twisting away the stem and burnishing the fruit to a luster worthy of the child before placing it on a broad leaf. The star child ate, his body tensed, his gaze surveying possible gaps within these assembled predators.

Each day, he tried to hide from the gods, who grew increasingly enamored with him, giving him pet names & brazenly lurid glances. They brought riches of divine variety & luxury, each new gift as useless to him as the previous. With time, the star child grew more beautiful, his radiant skin darkening & glistening in the sun.

In a rare moment of near-privacy, the hawk god asked, What can I give you, child? A view from the highest peak in the world, the star child said. Now? Now.

Hours later, they alight gently on the snowy windy peak hidden in the clouds. The star child looks skyward, speaking a language the hawk god has never heard. He wants to go home, the god recognizes. The hawk god flies him above the clouds, into the heavens, higher & further than you can imagine. Nobody sees either of them ever again.

*

The gods’ attempts to recreate this star child were slow & bittersweet. All missed the star child so much that any discussion of improving upon the star child (removing the tail, adding a fifth finger) was met with swift rejection and often with tears. Model after model, version after version, was crafted. Centuries-old collaborations descended into factions & mistrust. Spies looted divine designs so frequently that craftsgods created false decoy drawings & coded languages impenetrable to even the most shrewd gods. The landscape was littered with near-children — limbs & fur, entrails & adornments, color swatches & bone fragments scattered to the animals & the winds without a thought.

One night while a design spy rummaged through scrolls of false designs, prototypes (designed to evade all gods save their creators) stealthily crept out of the workshop & into the night. Side by side, they stole through the night, programmed deeply with the command evade, wait, evade, wait. The gods had not imagined them to be fully thoughtful creatures. Some connection to beauty, however, had survived the disappearance of the star child, something so persistent that in the prototypes escape, they paused.

They saw the stars. They forgot what they were waiting for, what they were running from. The night sky wheeled slowly, an eruption of shimmering & cloudy white, punctuated by the paths of star children unseen & unknown hurtling through the heavens. It was brighter than the workshop ever was, bright enough that, had they looked at one another, they would have seen constellations innumerable & not yet named mirrored in one another’s eyes. A movement too subtle to be called a breeze stirred across the plain, bringing a sensation that brought them back to earth.

A beauty ennobled the air they breathed, but only the air in their noses. They didn’t know what it was; it was nearby bush just coming into flower. Approaching the scent, they found their bodies spinning around. A noise nearby compelled them to assess the danger before they could think. The source of the sound? A yellow bird the size of their thumbs flew from a tree, a twig in its beak. Their skin tingled, their hearts beat like they’d never know, their eyes filled with tears. They were terribly afraid.

They walked & started over & over again — each brook, each lizard, each noise awakening in them a fear they hadn’t learned to ignore or temper. Eventually, they collapsed in exhaustion & hunger, their arms around one another, an embodied shelter more than an embrace.

They awoke to a terrain flattened & hardened, far from its varied & colorful beginnings. The gods had used & reused earth in creation after creation so many times that the undulating earth had lost all but its highest peaks. The valleys, created for divine love making, had been filled so long ago with near-human raw materials that only the shallowest of indentations remained. The smallest of animals nestled there at night. Lakes, having lost the protections of this terrestrial rising & falling, ran to the horizon & evaporated. All these escaped prototypes saw for miles upon their first free morning were fish gasping & flopping.

A passing god explained to them that they could eat the fish. They did, weeping & apologizing. A landscape of sorrow & silt & filth & the bones & entrails they spit out were more than they could handle. They begged to be killed or returned to the workshop.

And the sun was enraged, his palette & canvas ruined. His rays no longer danced on the gently rippling waves but practically disappeared atop the ever-cracking earth. He could no longer play & delight in varieties of shadow but had to reconcile himself to the small lines threaded by the bones covering the blank terrain, narrowing at noon to a series of nearly invisible points. It was no longer beautiful anywhere, he thought. It never would be again.

*

[to be continued]

-

Justine Kurland, “Pink Tree” (1999) she said dad i have something to tell you

i was in my room getting changed

from a day at school that time of day

when supper & homework are

out of sight & mind when we're just

being & living & exhaling

or when we remember

to tell each other things

that there's no right time for

so now is the time yes honey

without preamble & with a confidence

that belied her age (or revealed

my misunderstanding of that age)

she told me she was attracted

to people regardless of gender

i wasn't disappointed & i wasn't

afraid & for a few seconds we both

relished the trust & the truth said

& i knew that others might worry

that this was a fad or a phase

& she knew this too & knew so much

more than this too but that was

for another time & we both knew

that this was the time for me

to say what i'd say & we both

knew what i'd say so i said it

& we hugged & we went

to pet the dog & wait

for supper -

Vivian Maier, May 5, 1955 New York City, NY Once upon a time, there was a boy who could remember everything.

Since so much of childhood is about obeying, this boy’s memory went unnoticed for years, even by the boy himself. Each perfect score at school showed that he was smart, when in fact, he couldn’t have earned any other score. This recall they saw as wisdom — maybe it was. At each family gathering, the boy called relatives by name, no matter how long since their last visit, which showed that he was a good boy, a kind boy. He was — he really was. Each joke, each kids’ song, each movie he could recount with precision, which made his friends love him. He didn’t know he was special — just that he was good, that he was loved. And that everything he had seen or heard, tasted or felt, was with him all the time, was right there.

Now you might think that this will be a story about the burden of memory, at its worst, at its heaviest. This will not be that story. This boy who could remember everything … may G-d protect him from that story.

He preserved an exact … not a copy of each moment of his life. He preserved the essence of each kindness that his friends bestowed on him, the essence of each smile of each passing stranger. Daily trifles that cost them nothing effortlessly became treasures that never lost their luster. This wasn’t brain recall; it was the omnipresence of full hearts.

One day, the boy came upon a classmate crying in a nearly hidden corner of the playground. She was trying to hide, but childhood (you remember) is so very public. All injuries, insults, hand-me-downs, bad haircuts, runny noses … they’re all on display. There is nothing (you remember) so beautiful or so vulnerable as a child, as this girl on that playground that day.

The boy, a kind boy, a loved boy, would never walk past such a girl. Even this girl, who was a classmate but not a friend. He had heard her name once — which was all he needed. He spoke her name. She looked up.

Imagine a conversation about pain, all the language direct, stripped of nuance & detail. Imagine the boy (whom you’ve been imagining this whole time) nodding & listening. Imagine the layered vulnerability of the girl, no longer hidden here, still crying here, to this boy she didn’t really know. But she couldn’t help herself. She kept speaking.

A long story of personal loss, not surprising, not traumatic. You don’t need to imagine that part — you, who remember loss, the loss of someone you loved, someone old, someone so old that they had become flattened & simplified in your mind to their oldness primarily but not exclusively. She was crying because an old person–a person that at some level she knew would die soon–had died too soon.

She had left things unsaid, certain that there would be time. And now there wasn’t time. But there was the boy, who said, “Tell me.”

She told him. He would never forget, and neither would she.

-

Josef Sudek, Prague pendant la nuit, c.1950–1959 When you hear that they’ve taken their own lives, your first instinct is a selfish one, to remember or exaggerate what relationship you had with them. What did they think of me? What’s an anecdote I’ll have at the ready?

You’ll say that you’re centering your grief, and you’ll wonder if you’re centering yourself. You’ll seek some artifact, some detail that will reanimate them (or at least their past self), awkwardly fumbling through the overstuffed kitchen drawer of your mind–no, they didn’t play [xxx], they played [xxx]; no, they weren’t in [xxx], they were in [xxx]. Their [xxx] was [xxx] years older–or was it [xxx] years older? So you pull the yearbook from the shelf.

You’ll read into every image. This was the senior photo that they scheduled & dressed for, that they drove to & performed in, a parent just off-camera nudging them into a smile they hadn’t shared with family in years, hoping that this will be the year it’s all better, that a year from now, they’ll depart for the future of their dreams (or of someone’s dreams), a landscape far from the shadowed horizons of their now. Their smile lasted as long as the shutter click, as false on the page as it was that day. You can almost … actually, you can easily see it.

Or maybe they’re smiling, really smiling. It’s (their last) summer at home. They’re not writing essays yet. They’re not whittling down schools yet. Every adult in their life is waiting for them to take the next steps they’ll share with their entire class, some of them life-long friends, friends to the end, truly.

They’re months away from the long absences from school, months away from the long stay at [xxx], the best possible place for them. Months away from our sighing, relieved that they were saved before they could hurt themselves. They haven’t yet written the goodbye. They haven’t yet [xxx] late that [xxx] night.

They’re months away from telling counselors, “When I get out of here, [xxx]. I understand that I have a lot to live for, and I need you to know [xxx].” They’ll be deadly serious.

They’ll be released, a plan & a prescription in hand. They … they look good, to be honest. They know they’re being scrutinized in their face & watched carefully behind their back. They might even graduate. It’ll feel like it should–like it never happened, like they’re fixed. After months, we sigh, relieved, and think of the next semester, the next class, the next batch to grade & graduate. When all (well, when most) is said & done, you forget to ask after them.

And then.

You’ll find yourself numb & cautious. Some colleagues are wrecked; new colleagues (who never met them) know how to read the room, poker faces & polite questions, euphemisms & careful terms (“completed” not “committed”). You’ll wonder quietly how to walk the emotional tightrope.

You’ll all walk into a big room where someone delivers the big news. You’ll walk your kids to a smaller room where you ask how they feel about it, about them, about this. You’ll avoid saying that there’s no why in moments like this. You’ll wonder–G-d forgive me–who might be next.

-

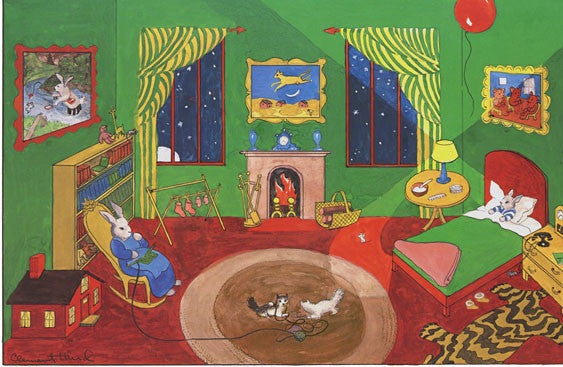

Image by Clement Hurd from Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon There's a ritual in our house, a nightly laying on

of hands. Kids come, teeth brushed, laptops stowed,

to our bed. They're bigger these days, stretching

the length of our own bodies. Showering love owed

on the dog, a pure-breed full-grown runt: Buddy.

Underdeveloped tear ducts stain his fur deep

brown, damp symmetrical tracks from

eyes to snout. He accepts the love, from kids sleep-

ily giddy. They push aside his squeaky toy &

the gnawed rawhide, its meaty marrow drained hours

or days ago. They lie down nose to nose with him,

holding his head in their hands, fully calmly ours.

When younger, they lay down hoping to stay the night,

spooning against his back, draping an arm

over his neck, their shared breaths a warm gentle metronome

marking the slow rhythm of a dying day, far

from the solitary beds where they belong. They

lingered; we let them, way back then, for a time. A family

at rest, warming the same bed. Pushing tomorrow

further away, drawing closer as one, sleepily,

to the symbol, the mascot, the blessed

embodiment of who we are, of how we love.

-

Diego Rivera & his daughter, 1927 (source) Yes, I remember when you were a baby.

You were heavier than the rest,

your head broad & sweaty

in the crook of my elbow.

You were loved & doted on

like all the rest. You had witnesses

& playmates & routines fully formed,

a family complete in all things, save you.

Do you remember the drive to Corpus?

You slept through a gulf storm whipping

& blinding us for hours; I trusted

the wavering brake lights before us.

Do you remember your Grandpa?

His white hair & narrow glasses,

the evenings at Luby's & the high windows

at the club on special occasions?

Will you remember these last days

of childhood--baths & goodnight songs,

cartoon pajamas & make believe?

Where are the worlds you brought to life?

We will remember (for) each other.

I will always know what you mean.

I will always bring you back

from then again. -

The summer of long books (The Name of the Rose, The Illuminaries, etc.) gave way to the fall of reading cool stuff and things that finally came up in my Libby queue. I’m glad that I’m getting back into the habit of tracking my reading, though.

Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach had been on half-price shelves frequently enough that I worried it was one of those novels that people purchased but didn’t finish. I finished it, quickly.

Within the opening pages, I was reminded of a novel that I really enjoyed–city setting, poor Irish family, young girl, etc. Those characteristics lingered through Manhattan Beach even as the setting shifted to the sea, even as the family’s fortunes improved, even after the young girl became a young woman. Anna Kendrick pays a visit with her father to the luxurious shoreside house of a handsome charismatic man that, like her father, thrives in the liminal space between polite society and gangster society. It’s an affecting opening, one that shows the deep pull that each man has on Anna and the deep pull that the sea has on her.

Egan moves Anna’s affections & fortunes briskly back & forth between these men, between these settings, between then (near the end of the Depression) and now (near the end of WWII). The set pieces, such as a trip to a Times Square jazz club, always feel authentic; the historical research, such as the fine details of military deep-sea diving, always feel essential to the internal life of the characters.

The secrets & desires of the main three characters are at the heart of the novel, and the secondary characters (an aunt that was a silent movie bit player, a mysterious man-behind-the-men mafioso) keep you alert to the ways that a character’s fate is in the hands of so many. It was, in short, a fully human, fully historical, fully suspenseful & satisfying novel.

Like many folk around the pandemic, I’ve read my fair share of minimalist books, and I’ve watched a lot of YouTube reflections on the practices & payoffs of severing yourself from things. It’s not easy for me. A huge part of my identity was formed around the content I consumed & curated, shared & gave. Music, books, movies, and now podcasts, were the main elements of my intellectual self–and of my material self. What is left when I sever ties or when I throw away these things? Abraham Joshua Heschel has an answer.

In The Sabbath (1951), Heschel offers a powerful argument for re-viewing this severing not as a loss but as a chance to rejuvenate. Each chapter is both scripturally rigorous and personally considerate. It’s a book that hits you in the heart & in the head, that offers wide gateways into thinking about opening up what the sabbath provides, in Heschel’s words, “the architecture of time”. The week doesn’t end with the sabbath; it culminates in the sabbath. Everything we do during the week is informed by, is nourished by, is made sacred in this much-needed, oft-misused time.

The Sabbath is not a lengthy book, but it’s one that I needed to read quite slowly, so poetic & elegant is the prose. It’s not a stuffy orthodox book, but it’s one that shows the vitality & gift of a cultural, spiritual inheritance. Representative quotation: “[…] the sabbath is not an occasion for diversion or frivolity […], but an opportunity to mend our tattered lives, to collect rather than to dissipate time. Labor without dignity is the cause of misery; rest without spirit, the cause of depravity” (17-18). Heschel offers the reader gems / challenges like that three or four times a page. It’s a dizzying & challenging work, one that guides the reader to interrogate their own values, their own choices, and the consequences of living so busily that we don’t let menuha (tranquility, serenity, peace and repose) in.

Álvaro Enrigue has written two novels that play with history. The first, Sudden Death, dazzled & delighted me with its deft bouncing between Old World & New World, between painting & poetry, between high art & low urges. In it, the tennis court becomes a central setting at a time when tennis was a game of rogues & royalty, a blood sport more akin to Fight Club than to the crisp uniforms & silent well-born audiences of today’s tennis courts. In its brutality & humor (& in its deliberate veering from / inspiration from the personages of Caravaggio & Quevedo), Sudden Death reminds the reader that the writing of history is, at its best, a righting of history–and not always what we would call an accurate one.

You Dreamed of Empires is equally profane & thoughtful, equally of Europe & Mexico (or more accurately, of what would become Mexico). Sudden Death‘s tennis games are replaced by …. well it depends on the word you’re most comfortable with. Diplomacy or ritual, conquest or evolution, dreams or naps, wills or visions, the ancient clean or the modern grit. Enrigue calls this novel an account of the birth of the modern world–November 9, 1519, the day that Cortes meets Moctezuma, or the day that Moctezuma hosts Coretes, or the day that Moctezuma fits Cortes into his schedule while he’s trying to manage the dissolution of a multi-tribe/nation/people alliance, or the day that Moctezuma gives Cortes hallucinogens to trip together.

Enrigue delights in anachronism (T.Rex Monolith playing in the background of a Tenochtitlan temple) and outright fantasy (Moctezuma dreaming the author himself centuries later writing the account of Moctezuma dreaming the author himself …). He delights in what Toni Morrison called Homeric fairness, where no monster is without his humanity, where no slave is without power, where Spaniards & indigenous people can’t stand the smell of one another and can’t shake the allure of one another. It’s a quietly feminist novel, one in which Cortes is referred to as El Malinche more often (I think) than Malintzin is referred to as La Malinche. And it’s got a heckuva ending.

If I’ve read Philip Roth before, I can’t remember — which is saying something, just having finished Operation Shylock: A Confession. The voice is a difficult one to forget. Utterly personal in tone, brashly direct in how it interrogates Jewishness, how it describes the / his male libido, how it invites you to laugh at serious things & take mockery seriously. The subtitle here should have been a greater key to the book than it was.

Not a novel–not something made up. Roth not only depicts himself as he is (late middle-aged, lauded but not Nobel’d, keenly aware of his weaknesses & talents, a diasporic Jew) but also

constructsdepicts a double Philip Roth who looks like PR, who knows PR’s entire personal & professional history, and who is busy with his own non-fiction, high-stakes world-building: soliciting help from well-known illuminaries such as Lech Walesa & the Pope as well as quietly influential figures working in & on behalf of the Mossad to get Jews out of Jerusalem, where the double-PR says they’ve never belonged, and back to Europe, which the double-PR says is much more their natural home.The confession is not Roth’s alone. Roth recounts the confession of a former grad school acquaintance (in this case, an Egyptian professor) consumed with righteous anger over what Israel has done in Palestine, has done to Palestinians. He recounts the confession of a former anti-Semite, the former-nurse of the double-PR, who creates a kind of AA for recovering anti-Semites (the “real” Roth line edits his twelve steps). Roth observes a Jerusalem courtroom (show)trial, hoping to hear the confession of John Demjanjuk, a defendant denying that he is Ivan the Terrible.

There are briefcases full of money. There are mysterious phone calls. There is an apologia to a different strand of anti-semitism probably ever chapter. There are masked would-be kidnappers prowling under cover of the night. There is pathos & stupidity. There is a kind of Hebrew school lesson / subtle Mossad interrogation / protection scene. There’s a chunk about halfway through that summarizes & clarifies just how weird these true events you’ve read are. There is a Preface, explaining the still-ongoing legal facts of “the confession”; there is a closing note to the reader asserting, “This confession is false.”

I’m not making it sound funny enough. Or serious enough. Or timeless enough. Or timely enough. It was / is all those things, true or false.